March

2017

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

24

Pipeline age and safety record

Pipelines are considered the safest and least expensive mode

for delivering crude to refineries, though even they can leak or

rupture if damaged. The majority of US pipelines were built

prior to 1970. When installed and maintained properly, steel

pipelines can last for many decades, though welds and

connection points can eventually become compromised. In

2011, after serious incidents with natural gas pipelines, the

US DOT and its PHMSA issued a call to action to accelerate the

repair, rehabilitation, and replacement of the highest risk

pipelines. The highest risk factors were age and material, since

many of the oldest pipelines were built of cast and wrought

iron rather than steel. The biggest threats to these lines is earth

movement, usually caused by digging, seasonal frost heave, or

changes in groundwater levels. PHMSA now reports on pipeline

miles by decade installed.

As Figure 14 illustrates, the majority of refined product

pipelines were built between the 1940s and 1970s. A large

percentage of crude oil pipelines were also built during that

time period, but there was a significant increase in construction

of new crude pipelines during the decades 1990 – 1999,

2000 – 2009, and now completed or planned for 2010 – 2019.

Much of this investment came about because of the need to

transport crude from shale plays.

The increase in oil transported by pipeline, combined with

the risk factors of age and construction material, has

contributed to an increase in serious incidents over the past

decade. Serious incidents rose from 107 in 2006 to 179 in 2015.

On the positive side, however, the volume of barrels spilled has

declined. In 1996, PHMSA reported 160 188 bbls spilled. This

declined to 137 052 bbls spilled in 2005. Over the past decade,

there has been an increase in incidents, but oil spilled dropped

to 102 424 bbls in 2015. Figure 15 displays this relationship.

Public concern over pipeline safety has increased. PHMSA

recently received authority to issue industry wide emergency

orders. Previously, PHMSA was allowed to issue corrective

orders to only a single operator at a time, but Congress in

June 2016 granted the agency broader emergency powers. The

US midstream industry opposed this. Pipeline safety came back

into the limelight in September 2016 with the Colonial Pipeline

failure in a remote area of Shelby County, Alabama, which

spilled an estimated 6000 bbls of gasoline. The company

responded quickly, sequestering the spilled gasoline in mine

water retention ponds. It reported no threat to public health

or safety. Unfortunately, in the process of repairing the

pipeline, a work team ruptured the line, causing one

fatality and several injuries.

Conclusion: the next oil price cycle

and US crude supply

The US’ downstream oil sector has undergone, and is

undergoing, major changes. The strength in crude prices

helped give birth to the US shale boom, which greatly

expanded the supply of domestic crude and cut into

foreign crude import requirements. Many of the new

crudes were being produced in frontier areas that were

not connected to the established pipeline network

upon which US refineries relied. The refineries that had

access to the less expensive crude feedstocks achieved

high utilisation rates. The other refineries sought access

via less conventional transport modes, such as rail car,

tanker, barge, and truck. New pipeline connections

were built as well. Safety issues arose in areas where

crude had not been transported in such vast quantities

before. Concerns over public safety continue to exist,

and it remains to be seen whether infrastructure

investments and public policy changes will improve the

safety of oil transport.

The surge in US crude production contributed to

the global glut, however, which motivated Saudi Arabia

and other OPEC countries to launch a price war. The

lower prices eventually shut in some US production,

changing the crude diet and the modes of delivery. US

crude inputs to refining grew in 2016 while prices were

low. The question facing the industry is whether prices

will increase and remain high in 2017 because of the

OPEC and non-OPEC production cut pact. Or will high

prices tempt additional US domestic crude back into

production, and will this in turn cause prices to

weaken? Supply, demand and price continue to

interact.

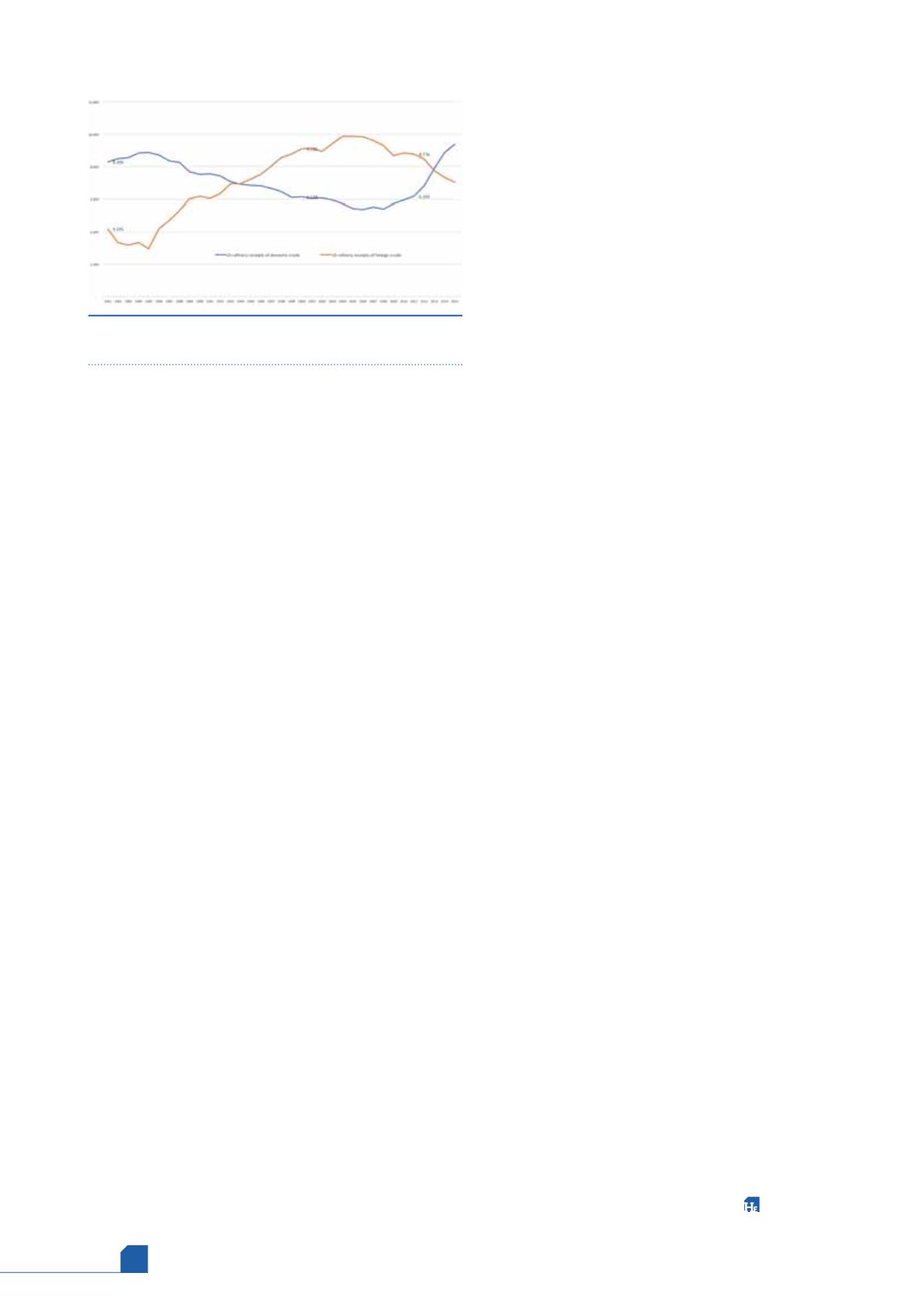

Figure 16 illustrates how the cycle of US refinery

receipts of crude oil has shifted. In the 1980s, US

refiners received approximately twice as much

domestic crude as foreign crude. In 1981, domestic

crude runs averaged 8.306 million bpd, while foreign

crude runs averaged 4.195 million bpd. By the late 1980s,

US crude production entered into a period of decline

that was considered inescapable. Foreign crude receipts

rose steadily, reaching 9.887 million bpd in 2004.

Refinery receipts of domestic crude dropped to

5.721 million bpd in 2004. The shale boom changed this,

and it reversed the roles once again. In 2015, refineries

received 9.391 million bpd of domestic crude and

7.061 million bpd of foreign crude. In 2016, another

reversal seemed possible. US crude production was

declining, and foreign crude imports were rising. If the

OPEC-led price war had continued, it is possible that

US production would have entered into another period

of decline, and that foreign imports would have risen

again. Now, as 2017 commences, the global supply and

demand balance is in flux, and it remains to be seen

how the cycle of foreign crude vs domestic crude

continues in the US downstream sector.

Figure 16.

US refinery receipts of domestic vs foreign

crude; the shale boom causes the reversal.