March

2017

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

20

Figure 10 looks first at deliveries of foreign crude to US

refineries. The most important transport mode is, as might be

expected, tankers. When US domestic crude production was

declining, foreign crude imports rose. The percentage share of

tanker deliveries rose from 26% in 1985 to 47.8% in 2005. In 2005,

tankers had nearly caught up with pipelines, delivering

7.319 million bpd of crude vs pipeline deliveries of 7.387 million bpd.

After 2005, however, tanker deliveries of foreign crude slid steadily

down. In 2004, foreign crude deliveries by tanker had been

6.535 million bpd. This dropped by an incredible 2.612 million bpd,

plummeting to 3.923 million bpd in 2015.

The change in crude logistics was caused by the shale boom.

Domestic crude deliveries began to fall because US crude

production had been falling. Figure 11 displays the trend in US

refinery receipts of domestic crude by transport mode. Pipeline

deliveries peaked at 6.804 million bpd in 1985. They declined for

the next two decades, hitting the nadir at 4.325 million bpd in

2005. The ensuing decade from 2005 – 2015 witnessed a major

resurgence in pipeline deliveries, which soared to 7.168 million bpd

in 2015 as production from shale plays began to crowd into the

system, seeking refineries.

In the early days of the shale boom, pipeline capacity and

connections were unable to cope with the influx of new crudes,

and there was a scramble to correct this. Pipelines are usually

regarded as the cheapest and safest oil transport mode, but

building and expanding pipelines takes time. As Figure 11 shows,

there was growth in all other modes as well.

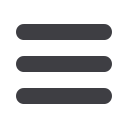

Because pipelines and tankers are such dominant modes,

Figure 12 presents the data for barges, tank cars, and trucks only.

The use of these modes surged in response to the shale boom,

growing from 604 000 bpd in 2004 to 1.779 million bpd

in 2014. The total fell to 1.602 million bpd in 2015,

however, corresponding with the decline in US

production and the completion of new pipelines.

The transport modes used to deliver crude to US

refineries have changed enormously over the past decade.

Before the shale boom, it was accepted that foreign crude

receipts would continue to grow, and that the common

modes would be tanker deliveries and pipeline deliveries.

The increase in US crude production over the past decade

strained the transport infrastructure, and refineries began

to receive more crude via barge, tank car and truck. Tank

cars were needed, for example, to deliver crude to

refineries on the East Coast and West Coast that were not

connected by pipeline to the main crude producing areas

in the centre of the country. But the use of these modes

has tailed off. First, the pipeline capacities and

connections have been expanded. Second, US production

has fallen. Many forecasts expect that the production

decline has not yet ended. If this turns out to be true, it is

logical to expect that there will be continued easing of

domestic crude transport capability, which will reduce

reliance on the more expensive modes of barges, tank

cars and trucks. If, on the other hand, higher prices in 2017

bring a resurgence of crude production in areas not yet

tied to pipeline networks, reliance on these modes may

resume.

Crude oil transport by rail

As LTO production from shale plays began to surge, US

crude transport infrastructure was strained to deliver

the new crudes to refineries. This was particularly the

case in frontier producing areas such as the Williston

Basin and the Rocky Mountains. As noted, many

pipelines were either full or did not connect with the

new output. Crude transport by rail was looked to as an

alternative mode of transportation. The expression

‘rolling pipeline’ came into use. Rail offered flexibility

that some pipelines could not. For example, there are no

crude oil pipelines that connect the Bakken crudes with

refineries in California. Building a 1500 mile pipeline

from North Dakota to Los Angeles would be

extraordinarily expensive, and it would take a feat of

engineering to get it across the Rocky Mountains. There

are many railroad connections, however, and refiners

looked to rail as a means to gain access to less expensive

domestic crudes.

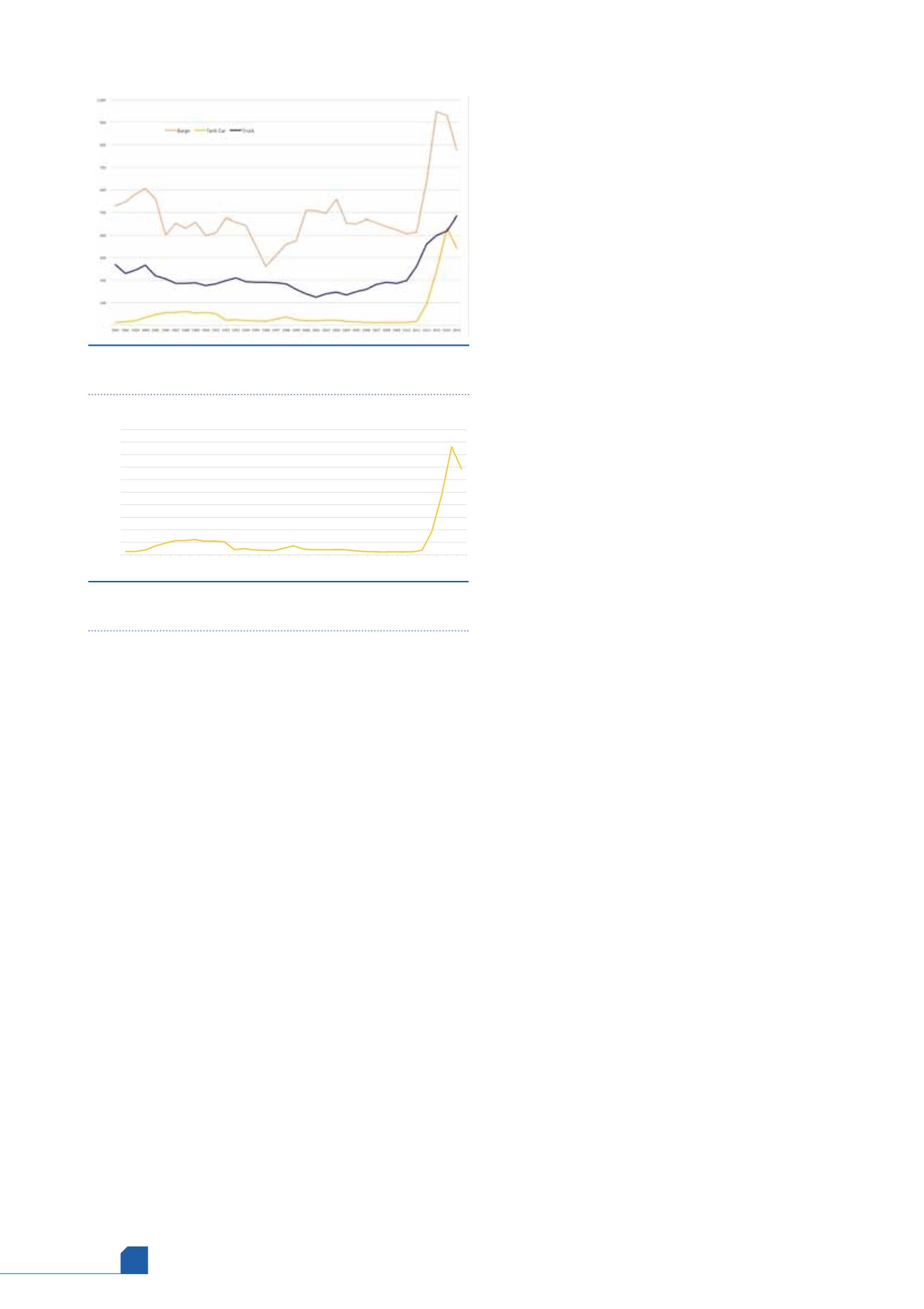

Crude transported via railcar grew quickly. According

to the US Department of Transportation (DOT),

9344 carloads terminated on US Class I railroads in 2008.

In 2014, this had soared to 540 383 carloads. As Figure 13

shows, US refinery crude receipts by tank car jumped

from 18 000 bpd in 2011 to 94 000 bpd in 2012, to

239 000 bpd in 2013, and to 431 000 bpd in 2014. In 2015,

however, crude by tank car declined to 343 000 bpd.

There was less demand for rail transport, one reason

being that additional pipeline connections had been

completed.

It is also possible that safety concerns have been

turning shippers away from railcars. The rapid increase

!

&!

"!!

"&!

#!!

#&!

$!!

$&!

%!!

%&!

&!!

"*)" "*)$ "*)& "*)( "*)* "**" "**$ "**& "**( "*** #!!" #!!$ #!!& #!!( #!!* #!"" #!"$ #!"&

""

"(

*$

#$*

Figure 13.

Rise and fall of US refinery receipts of crude oil

by tank car ('000 bpd).

Figure 12.

US refinery receipts of crude by mode,

excluding pipeline and tanker ('000 bpd).