March

2017

HYDROCARBON

ENGINEERING

16

signed at its 30 November meeting. On the eve of the

meeting, the market assigned only a 30% chance that OPEC

would be able to reach agreement. When OPEC defied the

odds, and signed the production cut agreement, prices

jumped. After the successful agreement, and with the

inclusion of the non-OPEC countries, the average price of

WTI crude rose to US$51.97/bbl in December 2016.

These increases in price are also reflected in Figure 3.

Rather than continuing on the downward path, US crude

production began to rise again by late 2016. It averaged

8.77 million bpd in December 2016, approximately

340 000 bpd higher than it was at its low point in July.

US refinery inputs and crude supply

The rise and fall in US crude production, and the location

of the crude feedstocks, is having a marked impact on US

refinery inputs and utilisation. Figure 5 presents the trend in

US refinery inputs of crude, natural gas liquids (NGLs), and

other feedstocks. Unless otherwise noted, the data used

for 2016 is the January through October average published

by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). In 2016,

crude inputs were 1.6168 million bpd. NGL inputs were

505 000 bpd, and this level has been fairly stable over the

past decade. Other inputs were 2.29 million bpd.

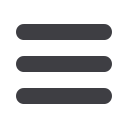

The ‘other inputs’ category has grown significantly,

rising from 1.238 million bpd in 2006 to 2.29 million bpd in

2016. These non-crude inputs are mainly geared toward

meeting requirements for renewable fuels. As shown in

Figure 6, this included 916 000 bpd of fuel ethanol,

62 000 bpd of renewable diesel, and 709 000 bpd of

gasoline blending components. Together, these feedstocks

account for 74% of the ‘other input’ category. Unfinished

oils are another important non-crude feedstock. These are

mainly heavy gasoils and residuum used as feedstock for

cracking units. Net inputs of unfinished oils averaged

383 000 bpd in the January – October period.

Crude inputs dropped from 15.242 million bpd in 2006

to 14.336 million bpd in 2009. At that time, the US and

many other countries worldwide were in the grip of a

severe recession. As the recovery progressed, crude inputs

also rose, reaching 16.188 million bpd in 2015. Current year

inputs have been similar to 2015 inputs at 16.168 million bpd.

Impact of easing crude export restrictions

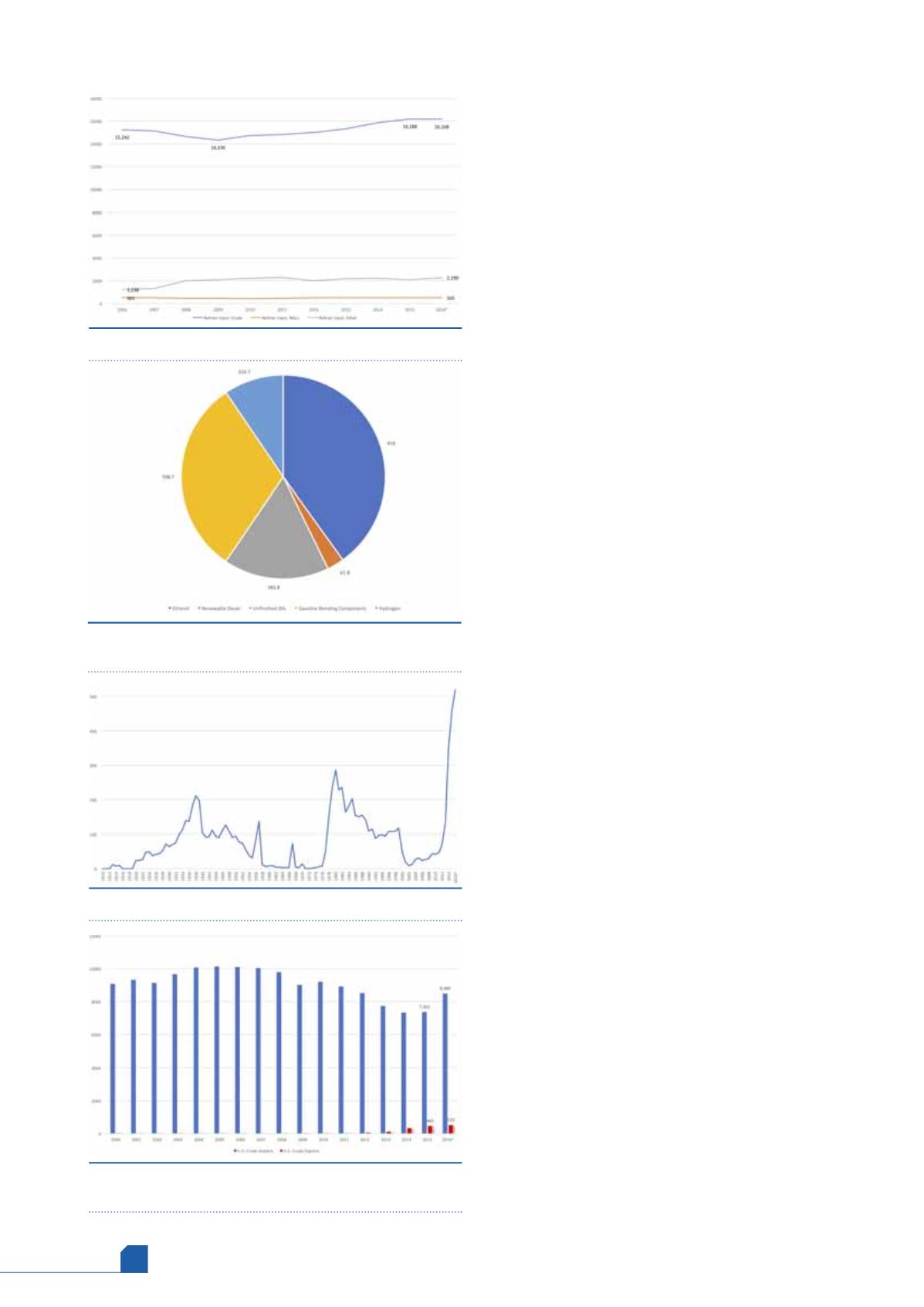

The year 2016 brought a new twist to US crude supply that

should increase market efficiency. In late 2015, the US eased

restrictions on crude exports. This was often mistakenly

termed ‘lifting the export ban’. In reality, crude exports

were not banned, but they were restricted to certain

trades, such as trade with Canada, exports from Alaska

state waters, certain volumes of California crude, and other

cargoes that were specially permitted. The US has been

exporting crude for over 100 years. Figure 7 shows the long

history of US crude exports since 1910. The easing of

restrictions caused a major surge in exports in 2016. They

skyrocketed to 520 000 bpd during the January – October

period.

The export restrictions had been supported by those

who believed that it would increase US crude supply

security. But with a world seemingly awash in oil, this

Figure 5.

US refinery inputs ('000 bpd).

Figure 6.

Refiner inputs of key non-crude feedstocks

('000 bpd).

Figure 7.

US crude oil exports 1910 – 2016 ('000 bpd).

Figure 8.

As US crude exports rose, so did crude imports

('000 bpd).