Africa. The US and Europe are still trying to firm up a grand

strategy to counter the combined China-Russia challenge.

In contrast, India suffered a sharp decline in its

international prestige towards the end of 2019, when the

government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi passed a

new citizenship law that was seen as discriminating against

Muslims. This could affect its efforts to improve energy

security through better ties with Middle East oil producers.

Similar to his predecessors, Mr Modi has struggled

to improve India’s energy self-sufficiency, as the country

continues to depend on oil imports to meet rising domestic

consumption. Attempts to draw oil investments from Saudi

Arabia and the UAE have yet to yield substantive results.

Uncertainty in Saudi investment

Despite the recent flurry of announcements about impending

deals, Saudi Arabia is still no closer to making its first

investment in India’s 5 million bpd oil market.

State-owned Saudi Aramco said it has signed an agreement

to store crude oil in one of India’s underground terminals while

it aims to become a minority partner in the oil and chemicals

business of privately-owned Reliance Industries Limited (RIL).

There is also talk of Saudi interest in taking a stake in an Indian

state-owned oil refinery, as well as participating in the retail

fuels business in Asia’s second largest oil market.

For now, the deal closest to reality is Saudi Aramco’s

proposal to store 4.6 million bbls of its crude in the

18.4 million bbl Padur terminal in the southwestern state of

Karnataka. Saudi Aramco signed the agreement with Indian

Strategic Petroleum Reserves (ISPRL), the operator of the state-

owned terminal, during Prime Minister Modi’s visit to the Saudi

Kingdom in late October 2019.

The quantity to be stored is small, making the risk

acceptable to both sides. But despite hopeful reports in the

Indian media, Saudi Aramco is unlikely to be interested in

purchasing New Delhi’s 53.29% stake in Bharat Petroleum Corp.

at a reported price of US$10 billion.

The deal that everyone awaits is Saudi Aramco’s proposed

acquisition of a 20% stake in RIL’s downstream oil and

petrochemicals business for US$15 billion. This was expressed

in a non-binding letter of intent signed by the two companies

in August 2019.

“Saudi Aramco and RIL have a long-standing crude oil

supply relationship of over 25 years,” said RIL. To date, the

Indian firm has purchased over 2 billion bbls of Saudi crude

for processing at its refinery in Jamnagar, in the northwestern

Indian state of Gujarat.

If a deal is concluded, Saudi Aramco would commit to

supply as much as 500 000 bpd of crude to RIL’s refinery on

a long-term basis. Most importantly, it would send a signal

that India is serious about opening its strategic oil industry to

foreign and private investments. That hope was undermined

on 20 December 2019, when the Indian government applied

to the Delhi High Court to restrain RIL from selling off its oil

and gas assets. It affirmed the industry’s suspicion that the

decades-long courtship over joint oil investments between the

two countries has largely been a charade.

While India’s oil market continues to grow, private

companies, especially international majors, are wary of making

large investments due to the government’s active role in

‘managing’ the industry and controlling oil prices. Indian oil

refiners and retailers are forced to subsidise prices at the

pump, resulting in their suffering massive losses every year. A

Saudi investment in India’s hydrocarbon sector may yet be out

of reach.

An increase in oil demand

India is unlikely to resolve its energy supply challenge for at

least another 20 years, judging by the latest oil forecast issued

by the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

The cartel predicts that between 2018 and 2040, India will

have the world’s fastest growing oil market, with consumption

expanding at a rate of 3.58% per year. Other countries will

trail far behind, including China, which is projected to increase

its oil use by a ‘mere’ 1.36% per year over those 22 years,

according to OPEC’s World Oil Outlook 2040. Rather than

wear this as a mark of achievement, India’s state planners

will be worried that they are failing to rein in the country’s

runaway energy demand.

If OPEC’s prediction holds true, India will be consuming

10.5 million bpd of oil in 2040, more than double its 2018 rate

of 4.7 million bpd. Over that same period, its share of the

world’s oil market will rise from 4.8% to more than 9.2%.

Even with the prospect of the US becoming an important

new supplier, much of India’s oil will still have to be imported

from politically unstable producing countries in the Middle

East, Africa, and Latin America, as well as Russia.

Owing to its inability to attract sufficient foreign as well

as private capital into the oil sector, India’s dependence on

imports reached a record high of nearly 85% in 2019. There is

little indication that this high level of import dependence will

decline much, despite Prime Minister Modi’s promise to boost

domestic production.

Since taking office in 2014, the Modi government has

overseen a steady decline in India’s domestic oil production,

from 905 000 bpd to 869 000 bpd in 2018, according to BP.

Over the same period, the country’s proven oil reserves have

fallen from 5.7 billion bbls to 4.5 billion bbls.

Foreign companies remain wary of

making big bets, as they are not fully

convinced the government is ready to

allow private capital to take a bigger

role in an industry deemed strategic to

national security. But the clock is ticking

fast as India’s oil appetite remains strong,

driven by its young population and a fast-

growing economy.

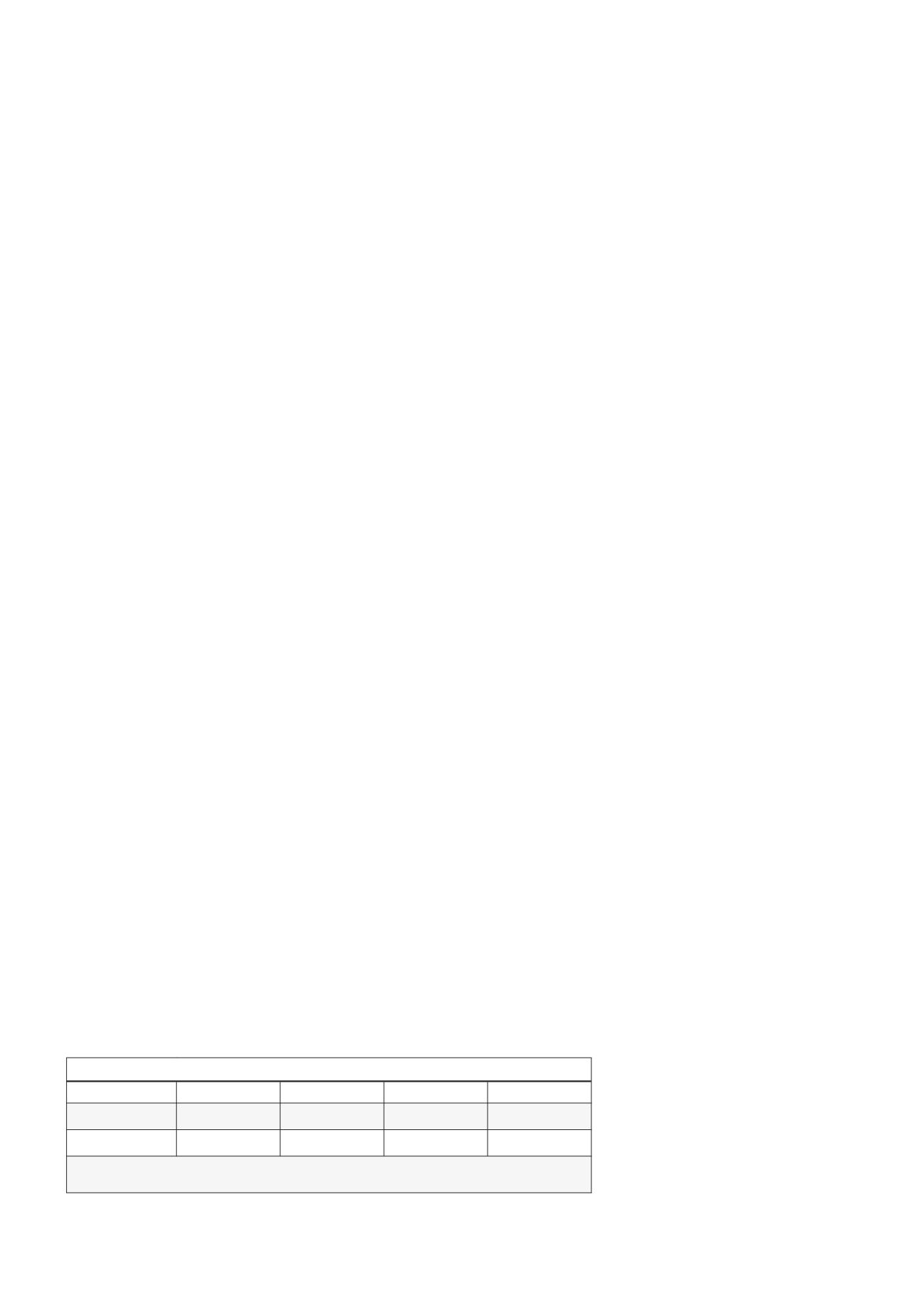

Table 1. IMF’s projections for CCA’s economic growth

2018

2019

2020

2021 - 2024

Energy exporters*

4.1%

4.3%

4.4%

4.5% per year

Energy importers**

5.2%

4.9%

4.5%

4.5% per year

*Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

**Armenia, Georgia, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan.

14

World Pipelines

/

MARCH 2020